(CNN)You might call it a kind of social movement: They call themselves, futurists.

Futurists

say they look at life with a perspective that they consider to be 5 to

10 years ahead of the rest of us. Obviously they're fascinated by the

cutting edges of technology. But many of them are fascinated by the idea

of bridging technology and the human body.

"I'm

essentially living in the future," says Anders Sandberg -- a research

fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University. "I'm

trying to think ahead. But prediction is really hard. The interesting

questions is: Can we learn what we are actually able to predict and

which areas we should give up on?"

More stories about the future of science, tech and medicine

Some futurists go one step further. They experiment on themselves.

"We

are not the endpoint of evolution. We should enhance ourselves," says

Dr. Andrew Vladimirov. Based in the United Kingdom, Vladimirov conducts

research on himself and others using a device that shoots an infrared

laser beam through the skull into the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

The device is designed to learn more about "what our brainwaves are for

and what is consciousness," Vladimirov says.

Pioneers: Will gene "editing" change society as much as computers?

Then

there's Neil Harbisson -- a self-described human cyborg who had a

doctor surgically implant an antenna into his skull in 2004. Based in

Catalonia, Spain, Harbisson says the antenna allows him to hear colors.

For example, blue sounds like the musical note C, or C sharp, he says.

What's

a futurist? Depends on who you ask. Vladimirov says futurists are

basically trying to alter the course of events at least 10 years ahead

or more.

Self-described futurist Amy Webb writes that

they're "a lot like journalists. Except that rather than reporting on

what's already happened, they report on what's starting to happen on the

fringe, and they analyze that information within the context of our

many changing environments."

Is the movement political? If you're Dirk Bruere, secretary of the UK's Transhumanist Party, the answer is yes.

Genetic engineering will present difficult

legal, moral and ethical questions for lawmakers, Bruere says.

Futurists need a party in the same way the Green Movement did, years

ago, he says.

"The fact that it's been very successful in influencing policy worldwide suggests maybe transhumanism can do the same."

Bruere hopes to see his party get 5% of the vote in parliamentary elections next year.

Psychology

The power

technology can have on human psychology can be profound. That connection

is the subject of research by psychologist/neuroscientist Dr. Caroline

Falconer of the University of Nottingham. She's developing ways to use

virtual reality to treat depression by having patients wear a

head-mounted, high-definition, 3-D display and a suit that allows

full-body computer tracking.

Patients

use this gear to spatially substitute their own bodies with an avatar.

Then, Falconer guides her patients to work with their avatars on

developing their self-compassion.

Mind control

Tiana Sinclair says she can control a small flying drone with her mind.

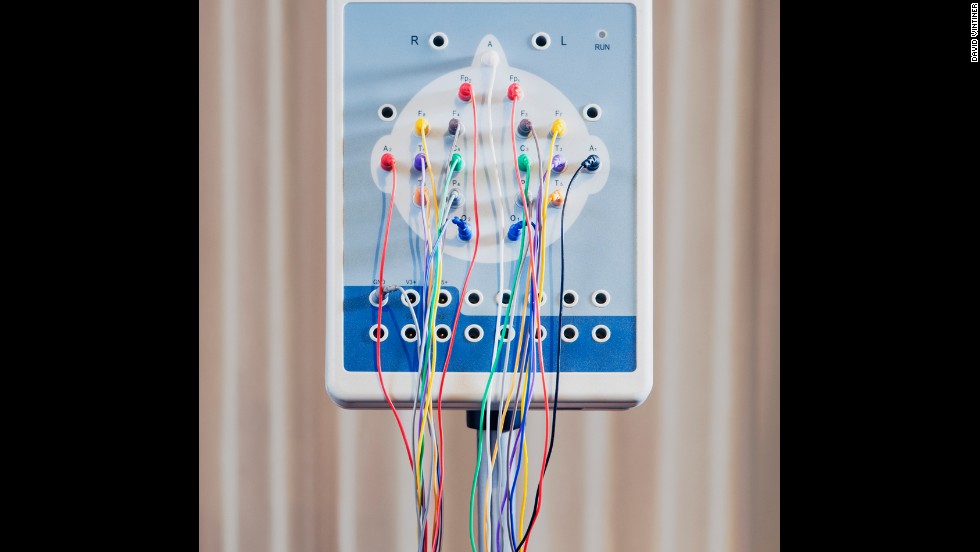

"Essentially

the drone is like a huge biosensor," says Sinclair, a UK-based start-up

founder. "It's like a huge EEG device" that senses alpha and beta

brainwaves. She says the drone is easier to control while trying to

remember something structured, like an equation or a song.

"But

really, futurism isn't about the gadgets, it's about the cultural

change and impact," Sinclair says. "I'm kind of a big believer that the

world is a little bit broken and we can solve its problems with the use

of technology."

No comments:

Post a Comment